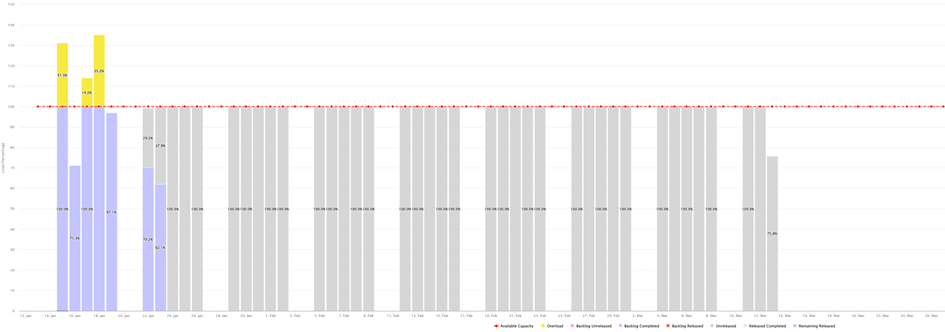

The graph below shows the production orders created for a line of strategic finished products in an aeronautics plant.

These are production orders, not planned orders.

Each bar represents one day. Blue bars are production orders released to production: the workshop has the right to work on them. The gray bars are orders created, but not yet released. This is a Master Production Schedule.

This graph represents the load on the critical equipment that paces the flow of this product line (the primary constraint on this flow). This constraint is at the beginning of the routing: in fact, production takes place within 24 to 48 hours of the work order release.

What can we see on this graph?

– Work orders have been released to the workshop for 7 days, whereas 1 or 2 days would be enough to get organized in the field.

– As we’re running late, we’ve loaded the first few days beyond capacity, and we’re keeping our fingers crossed.

– We created WOs over an 8-and-a-half-week horizon. So we defined precise dates, and generated a sequence, well beyond the next 48 hours.

Why do we do this, when we have stocks of the components that go into this finished product, when we have a robust replenishment discipline, and when in any case we have projections of requirements and risks of shortages that give us all the visibility we need to assess risks and make decisions over the coming weeks? Will creating OFs 8 or 9 weeks in advance help us?

The answer is no.

It’s going to cause us all kinds of problems, because requirements dates are going to change, and on the upstream side we’re also going to fall ahead or behind. Creating production orders 8 weeks in advance will just complicate our lives and add to our inertia.

If you analyze your industrial system and observe the number of production orders and purchase orders you have generated, and often released, at any given moment, you’ll get a good idea of the degree of inertia in process.

To be able to adapt nimbly, to take the necessary turns at the right time, you need to limit this inertia by generating orders only at the right moment – i.e. as late as possible.

The pilot of a helicopter, a fighter plane, or a Formula 1 car doesn’t perform a sequence of gestures predefined long in advance. He / She performs the required gestures at the required moment, to optimize the trajectory, knowing that the plane/car has refueled and that weather risks have been dealt with before departure. This pilot has also undergone appropriate training to deal with any situation.

The solution? Prepare your operating model well, structuring it so that you don’t need to make decisions too early. Define horizons well, educate and train teams, and reassure all players by demonstrating that reducing firm horizons doesn’t reduce the flow!