Do Tariffs Really Impact China’s Global Supply Chain?

Co-authored with Clark Banach, PhD

I recently had a fantastic discussion with Clark Banach, Program Director at Aletheia Research Institution and Futures Fellow at MERICS (Mercator Institute for China Studies), on the growing control over global supply chains that China is taking, as well as the ineffectiveness of tariffs on Chinese imports into the U.S. We co-wrote this blog and those who want to learn more, check out Clark’s working papers.

Tariffs, Industries Impacted, and the Global Supply Chain

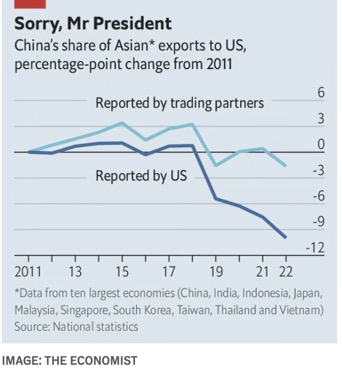

During the Trump Administration, significant tariffs were levied against China to curb the flow of Chinese imports into the United States and protect domestic producers against dumping and subsidized production. These tariffs were continued by the Biden Administration for several broader political objectives. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of the tariffs are questionable and the benefits may not outweigh the costs when considering the outcomes. It is difficult to determine the effectiveness of the strategy as both parties have an interest in reporting favorable outcomes. The Economist identifies variation in published figures by both parties. China reports that its exports to America rose by $30bn between 2020 and 2023, whereas America says its Chinese imports fell by $100bn.

Regardless of official numbers, the trade barriers established and maintained by recent US administrations have been less effective than originally intended and may not be the reliable political bargaining chip they were envisioned to be. How is this so?

The actual impact and effectiveness of tariffs can vary depending on the specific circumstances and the broader economic context. In this case there is comparatively little understanding about how China’s economy operates and the drivers of domestic production in an ocean of international competition. China has transformed into a relatively successful mercantilist state that competes externally while controlling economic affairs inside the borders of the country through SASAC (State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission). This special commission operates as a state-run holding company and focuses the means of production on trade surpluses and global economic growth. As of 2021, it is the largest economic entity in the world.

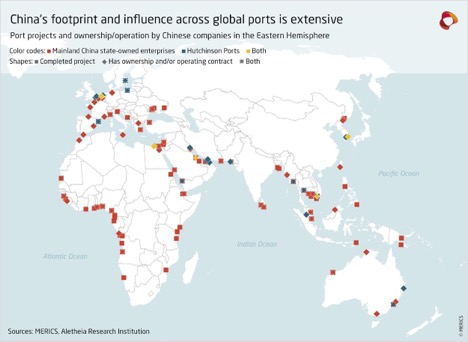

Despite efforts to liberalize the Chinese economy, domestic markets are still heavily controlled by 97 centrally owned companies that channel state capital into strategic economic sectors. This includes many of the enterprises that are critical to supply chain management. One of the largest entities in SASAC’s portfolio is shipping giant COSCO (China Ocean Shipping Company) – (think of a state-run Maersk!) The portfolio also includes terminal operators, container manufacturers and software developers that have established dominant market positions in global value chains.

Several SASAC enterprises have been successful in establishing control at deep-water terminals by winning concessions and terminal leases. This position then extends inland to other supply chain touchpoints as the benefits of vertical integration are sold to host countries on the grounds of cost savings. By operating the terminals and financing the development of ports, they can then offer the technology and equipment to manage the terminals and provide resources for industrial organization projects and inland logistics channels that include railways, roads and cross docking stations for truck shipments. At that point, Chinese state-controlled enterprises are in a position to exert a significant amount of pressure on host economies.

This influence can then extend to neighboring countries. For instance China developed a large port in Angola, after which the race to extend rail lines and truck routes through Zambia to Congo to export cobalt from mines they also control was quick to follow. Controlling the port means controlling the entry points to hinterland operations and the flow of goods out of the host country. Clark Banach, Program Director at Aletheia Research Institution and Futures Fellow at MERICS (Mercator Institute for China Studies), applied a structural gravity model to his team’s BLOCS data to identify that when Chinese firms operate all terminals in at least one port, the following trends occur:

- Exports to China: +76% increase after 12 years

- Imports from China: +36% increase after 12 years

- Exports to Rest of World: -19% decrease after 12 years

The growth in China’s control of ports, particularly in the EU, Middle East and Africa, is shown in a geospatial projection developed by Aletheia Research Institution and MERICS. This is a shocking level of growth, taking place right under our noses.

When the Trump tariffs were launched against Chinese imports, China was able to undermine these efforts using a collection of middleman partnerships. This additional tier in the global supply chain created income opportunities in emerging markets and passed through costs in a way that provided economic opportunities for both Chinese firms and willing partners. As a result, America currently understates its imports from China by 20-25%, and China has encouraged exports by cutting taxes on exporters. Thus, the attempts to “de-risk” trade with China across two administrations, despite being the cornerstone of their foreign policy, is not working out. A real de-risking strategy includes threading the needle between national security and economic security. At the moment the economic sacrifices of protectionism are not adding up to gains in our common defense.

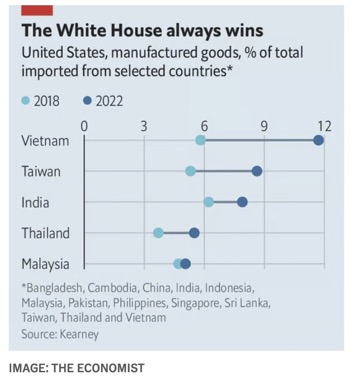

Another strategy used by China is to simply to reroute shipments through countries where America has fostered “friendshoring” relationships. For example, in the domain of advanced manufacturing products, officials are actively working to diminish China’s influence. Notably, the share of American imports from China decreased by 14 percent from 2017 to 2022, with imports from other nations gaining significant market share, as illustrated in the accompanying graph. However, a concerning aspect of this trend is the rapid rise in the share of Chinese imports into these countries as state-owned enterprises from China are establishing subsidiaries and exporting intermediate parts and components to these nations. During this time, China has increased its share of exports to the ASEAN (Association of South-East Asian Nations) block in 69 of 97 product categories. Even in Mexico, 40 percent of offshore investments in automotive manufacturing came from China, and China is exporting more than twice the volume they did five years ago.

In short, tariffs have had almost no effect on imports from China, and China has continued to increase its hold on global supply chains. Furthermore, when Chinese firms operate terminals they soon increase their buyer and supplier power and lock host countries into trade dependencies. A recent working paper by Clark Banach and Jennifer Pedussel Wu of Aletheia Research Institution also identifies evidence of trade diversion away from natural low-cost trade partners and toward Chinese firms as a result of terminal control. The challenge is that host countries benefit from the partnership with China in the short run – but at what cost? Once you commit, attempts to pivot away will be expensive and could lead to dramatic economic shock – a lesson regions will soon understand if they wish to maintain their autonomy.