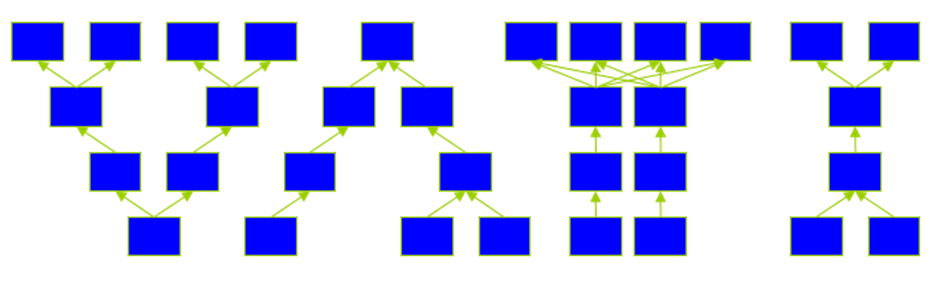

Your supply chain management model must be adapted to the profile of your production flows. There are four typologies are that are most common: V, A, T, and I. Understanding your company’s typology will help you assess how to pace it to market demand.

V-Shaped Profiles: Differentiate as Late as Possible!

If your flow is V-shaped, you start with a few raw materials, and from these few materials you will produce a multitude of finished products.

Example: Manufacturing aluminum profiles for carpentry elements. You start from aluminum billets, transform them into extruded profiles through dyes of various shapes, then lacquer profiles in the colors required by the final customer. Finally, the profiles are cut to length and assembled in the form of doors and windows. From the same billet, you will make an infinite number of custom finished products.

Another example: Manufacturing dental implants. You start from titanium bars, which you will machine, cut to length, assemble, sterilize, etc., and distribute globally. From the same titanium bar, you make multiple finished goods, sold in Europe, America or Asia.

V-shaped flows usually require expensive production resources in the early stages of manufacturing — the capacity constraints are there, very early in the process. Your challenge will be to allocate this capacity as best you can according to relative priorities in the downstream flow, pacing these constraints to the market’s aggregated consumption rate.

Beyond these upstream constraints, you need to differentiate as late as possible, so that you can make decisions as close as possible to actual consumption. If you have lacquered aluminum profiles in white too early, when you are receiving orders in abundance, it is lost — and you risk having to re-run an extrusion when you have white stock on hand. You’ve wasted your precious extrusion capacity. You will therefore place decoupling points — DDMRP buffers, in the lingo — as far upstream as possible and differentiate as close as possible to the customer’s demand, with short lead times. Your final processing steps will ideally be made to order, if that is compatible with your customers’ lead time expectations.

The Demand Driven techniques of inserting stock buffers and assigning relative priority will allow you to orchestrate an adapted model. If you are in an allocation mode, you will pilot your constraints at the beginning of the process according to the contribution margin per unit of work of these constraints.

A-Shaped Profiles: Synchronize at the Top!

When you are in an A-profile, you make a relatively small number of finished products from many components and sub-assemblies. Your main challenge will be to protect the point of the A, i.e., to make sure you are able to assemble your finished products without missing parts. The aerospace industry is an example of this type. It takes tens of thousands of components to make a plane.

Most of your effort and attention will be devoted to procurement, so that you have complete kits on hand when you assemble the final system. To protect the integration of your materials at the top of the A, you will organize and drive either stock or time buffers.

That’s because you need to protect the final integration rate — from the top of the A — and therefore subject the upstream branches to this final constraint. For example, you must align the entire upstream aeronautical chain with the aircraft assembly rate.

In your upstream branches, you can employ a wide variety of production processes, all with varying constraints and risks of “floating bottlenecks.” You must therefore stabilize your demand signal with appropriate downstream buffering techniques, and monitor the system load per period to make timely load/capacity balancing decisions.

T-Shaped Profiles: Secure the Modules!

The T-profile corresponds to an upstream fabrication of sub-assemblies and semi-finished modules. These modules are then combined in the final stage to produce the finished product, often in an assemble to order.

Automotive manufacturing and some configured electronic systems are examples of this typology.

Where should you position your buffers? Undoubtedly on purchased components — but above all on those semi-finished levels before assembly. After all, you must be able to count on the permanent availability of the most common modules in order to assemble any finished product in a short time.

If you manufacture to stock, you will minimize your inventory of differentiated finished goods and keep your main inventory at the semi-finished level.

Your final assembly must have capacity margins in order to adapt to demand — and you will integrate the consideration of upstream capacity constraints into the management of your sub-assembly buffer replenishments.

I-Shaped Profiles: Speed Up the Conversion Time!

In I-shaped manufacturing flows, several variants are realized, which correspond to the number of components. This is often the case in the process industry — chemicals, food. The routings are relatively simple, and similar from one product to another.

Your focus will be on ensuring component availability with appropriate buffers on raw materials, as well as on finished goods — and on optimizing throughput times. Your manufacturing will probably be in line, with one of the transformation steps giving the time of each flow.

Your entire flow will be driven by customer demand — to order or to stock. The difficulty lies in scheduling of your production lines, as a single line may be shared across a wide range of products. Grouping campaigns of similar products and implementing planning wheels will both be important levers of improvement.

The Implications of VATI Profiles

Do you recognize yourself in the above profiles?

The good news is that whatever your type of business, the Demand Driven techniques incorporated in Intuiflow will allow you to implement the right operating model.

To learn more about the characteristics and challenges of these different models and their adapted piloting modes, read chapter 8 of the Theory of Constraints Handbook: “DBR, Buffer Management, and VATI classification.”